One court says yes, but it’s complicated.

How quickly things change. Last week, I was all mellow about the gender pay gap.

Then, on Monday, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit issued its decision in Rizo v. Yovino, finding that salary history was not a legitimate “factor other than sex” to use in determining pay under the federal Equal Pay Act.

Even though I disagree with the rationale and actual outcome of the Ninth Circuit decision, I feel more conflicted than you might expect if you’ve read my other equal pay posts.

Here’s a phenomenon I’ve seen a number of times in real life. An employer has two long-term production line supervisors, John and Doris. Even though their length of service is the same, Doris is making significantly less than John. There must be a good explanation: Doris is a poor performer, she is part-time, she fell behind after taking maternity leaves, right? The client says no — Doris is great, she works full-time, and she has never had a gap in employment.

Then why the pay gap? It must be sex discrimination!

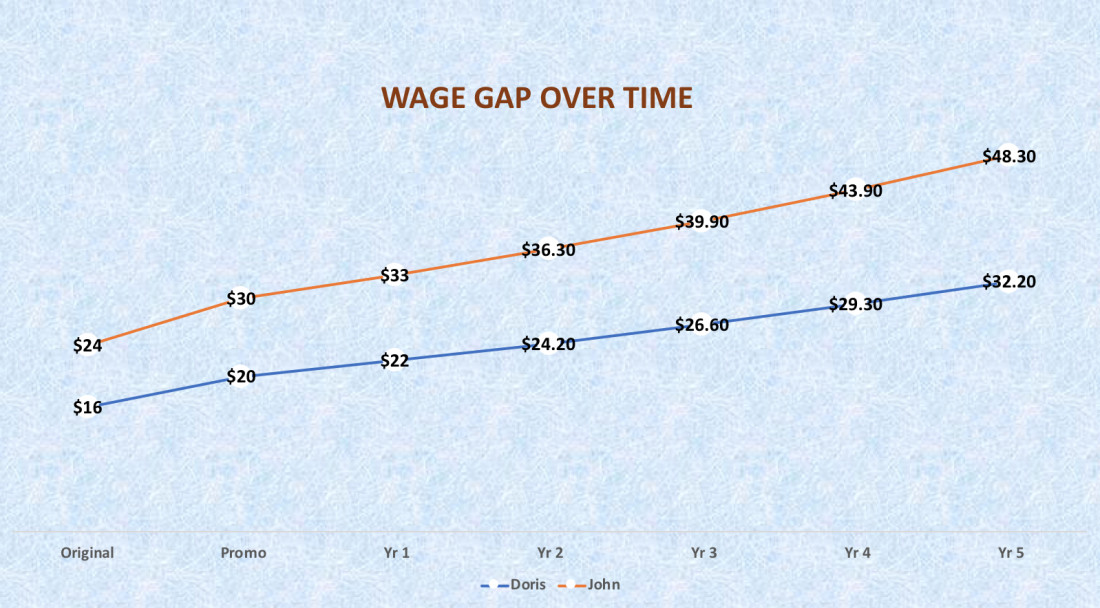

Actually, as it turns out, the gap is not due to “discrimination” but “salary history.” Before Doris was promoted, she was a machine operator making $16 an hour. Before John was promoted, he was a skilled mechanic making $24 an hour. Starting pay for supervisors was based on a percentage increase — let’s say 25 percent to make the math easy (I’m an English major, so I will probably still get it wrong) — so when these two employees were promoted to the SAME supervisory position, Doris’s pay went to $20 an hour, and John’s pay went to $30 an hour. Over the years, they each got the maximum merit and cost-of-living increases, but the increases were percentages of their prior salaries, which meant that over the years, Doris fell further and further behind John even though they were doing exactly the same job, and even though they were both doing very well at it.

The first time I learned that a client was doing this, I was horrified. “Why don’t you start all new supervisors at the same rate of pay?”

The client educated me. There were a number of reasons for doing it this way, none of which had anything to do with discrimination against women:

*A skilled mechanic would normally be expected to earn more than a machine operator, so the original pay gap when they were both hourly employees was justified.

*When you get promoted to supervisor, you lose the opportunity for overtime pay. The percentage was used, rather than a uniform “supervisor pay rate,” so that highly skilled employees like John would not lose money by taking promotions.

*The company wanted everybody to get a nice raise when they took a promotion to supervisor, so the percentage allowed that to happen, no matter how much the employee was making in his or her prior job.

Even though these answers all made sense and had nothing to do with gender, Doris is obviously still getting the shaft. She makes a lot less than John for doing exactly the same work as John.

Here are John and Doris, starting with their original hourly rates of pay, their promotion increases, and then increases of 10 percent a year for the next five years:

Even though they got exactly the same 10 percent increases upon promotion and each year afterward, their pay gap in dollars actually widened over the years. When they were both hourly employees, Doris was making $8 an hour less than John. But in Year 5 post-promotion, she was making a whopping $16.10 an hour less.

The same thing can happen in white-collar jobs, and in hiring if an employer uses “salary history” to determine the starting pay of an employee. If a person’s prior salary is lower than that of his or her counterpart, and if start pay in the new job is based on prior salary, then the person with the lower prior salary is not getting equal pay for equal work. As the Ninth Circuit opinion pointed out, the Equal Pay Act doesn’t require discriminatory “intent” — if the woman can show that she is getting less than a similarly situated male comparator, then she wins unless the employer can prove that one of the exceptions to the EPA applies. Those exceptions are

*A seniority system

*A merit system

*A system which measures earnings by quantity or quality of production, OR

*”A differential based on any other factor other than sex.”

In the Rizo case, the Fresno County (California) School System argued that salary history was “a differential based on any other factor other than sex,” but the Ninth Circuit said no way. In fact, the Ninth Circuit majority adopted a virtual “per se” rule that salary history is an inherently discriminatory consideration. Federal courts of appeal in other parts of the country disagree (rightfully so, IMO), and I hope this issue will be resolved by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Here’s why consideration of salary history is not necessarily discriminatory:

First, a lower prior salary is not always based on sex. Using my example above, what if the machine operator were Billy instead of Doris? The same gender-neutral pay policies would apply to Billy, and Billy would still be making a lot less than John for doing the same job. That would be unfair to Billy, but not sex discrimination, because Billy and John are both men. Or, what if Meghan were the mechanic instead of John? In the case of Doris and John, the pay discrepancy was correlated with sex, but it was not based on their sex.

(On the other hand, if the company had discriminatorily refused to hire women for mechanic positions, then I agree that the use of salary history in setting supervisor salaries would also be discriminatory.)

Second, as pointed out by my colleague Kacy Coble-Hernandez, there are all kinds of non-sex-based reasons for discrepancies in salary history. For example, I live in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, which has a moderate cost of living. Salaries here are probably likewise “moderate” on a nationwide scale — better than Mississippi, not as good as California. Let’s say I’m hired for a job along with a male candidate from San Francisco. All other things being equal, I would expect my counterpart to have been making significantly more money than I.

And why might our new employer want to give my male counterpart more money, even though he and I are equally qualified? Almost certainly not because he is a male, but almost certainly because the employer doesn’t want him to have to take a cut in pay to accept the job. Or, more accurately, they are pretty sure he’ll turn down the job if he doesn’t at least break even on it.

And what if the new job is in Winston-Salem, North Carolina? That means I can take the job with no relocation expenses or other hassles. I can quit my old job on Friday and start the new job on Monday. But my male counterpart is going to have to relocate from California to North Carolina, in addition to having to adjust to a “North Carolina salary” unless the employer accommodates him in some way.

All of these same considerations would presumably apply if my San Francisco counterpart were female instead of male.

So, yeah, I think the Ninth Circuit majority opinion went way too far. But at the same time, I’m guessing we can all agree that these “non-discriminatory” scenarios don’t really feel fair, either. If I ran the world, I’d rule that salary history can be used (as long as it isn’t a proxy for sex discrimination) but that employers must “close the gap” within a reasonable period of time, assuming that the performance of the two employees in the job is relatively equal.

(Don’t try my idea in the Ninth Circuit.)

Robin Shea is a Partner with the law firm of Constangy, Brooks, Smith & Prophete, LLP and has more than 20 years’ experience in employment litigation, including Title VII and the Age Discrimination in Employment Act, the Americans with Disabilities Act (including the Amendments Act), the Genetic Information Non-Discrimination Act, the Equal Pay Act, and the Family and Medical Leave Act; and class and collective actions under the Fair Labor Standards Act and state wage-hour laws; defense of audits by the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs; and labor relations. She conducts training for human resources professionals, management, and employees on a wide variety of topics.