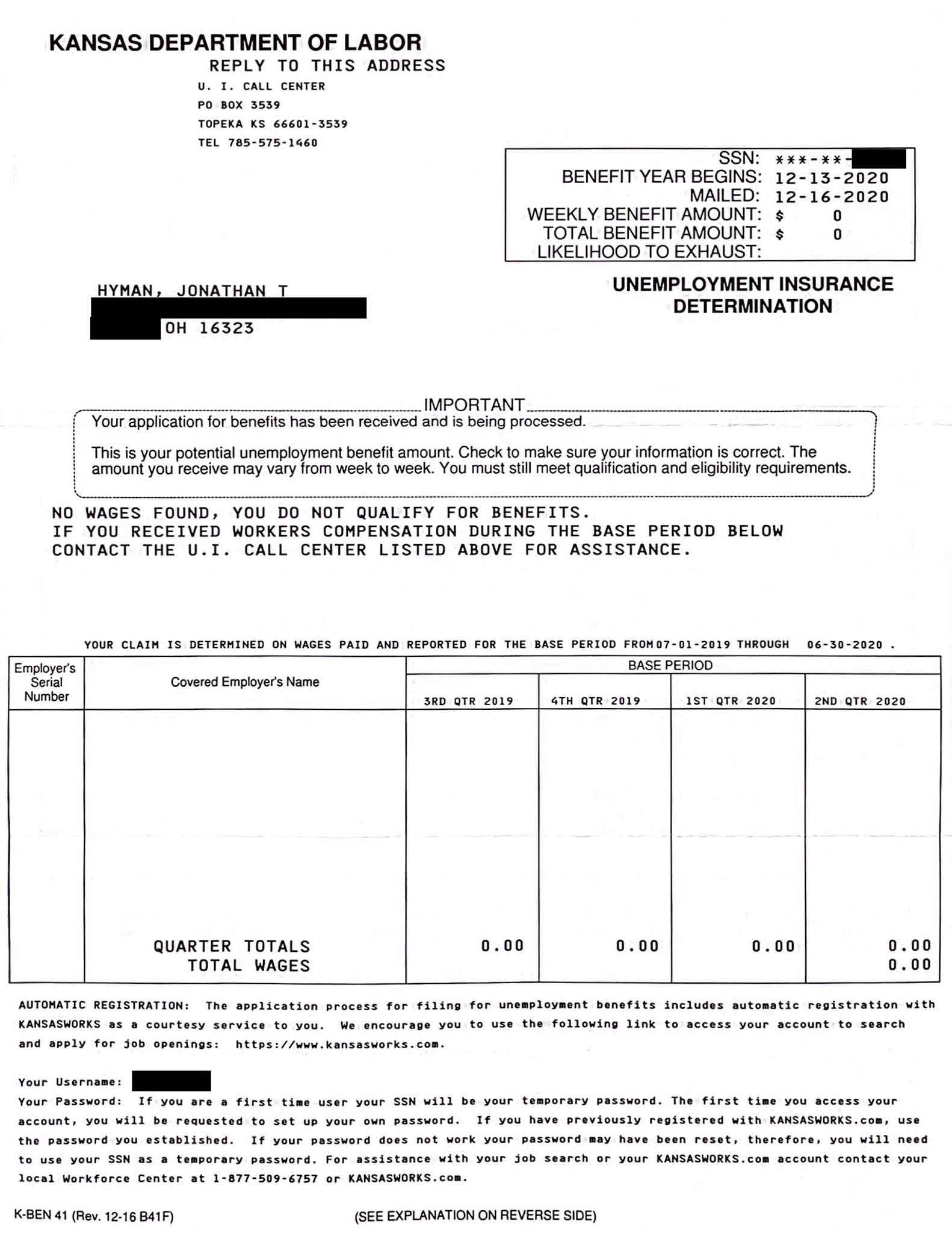

What’s wrong with this photo?

- I’ve never lived in Kansas.

- I’ve never worked in Kansas.

- I’ve never even been to Kansas.

- I never filed a claim for unemployment benefits with the State of Kansas.

1+2+3+4=unemployment fraud.

I’ve been the victim of identity theft and attempted unemployment fraud. And I’m not alone.

According to USA Today, fraudsters have stolen at least $36 billion from state unemployment systems during the COVID-19 pandemic. How? USA Today spoke to Mayowa, an engineering student in Nigeria, who says he’s responsible for $50,000 of these thefts, a mere fraction of his attempted frauds.

After compiling a list of real people, he turns to databases of hacked information that charge $2 in cryptocurrency to link that name to a date of birth and Social Security number.

In most states that information is all it takes to file for unemployment. Even when state applications require additional verification, a little more money spent on sites such as FamilyTreeNow and TruthFinder provides answers – your mother’s maiden name, where you were born, your high school mascot. Mayowa said he is successful about one in six times he files a claim.

“Once we have that information, it’s over,” Mayowa said. “It’s easy money.”

The reason it’s easy money is that a record number of out-of-work Americans has overwhelmed antiquated state unemployment systems. Simply, states can’t keep up with the record filings, operate under tremendous pressure to pay out claims to unemployed taxpayers, and work with decades-old technology that is myriad steps behind the strategies identity thieves use to bypass safeguards.

It does not appear that this scammer will succeed in collecting any money in my name. Since I have zero employment history in Kansas, it’s hard for that state to pay benefits in my name. Chalk one up to Nigerian engineering schools not teaching American geography. Some, however, are not so lucky. USA Today recounts the story of Kelly Maculan, a Chicago office manager, whom the State of Illinois threatened with litigation if she did not repay the $822 it had mistakenly deposited into a bank account based on a fraudulent claim filed in her name.

In the meantime, I’m left to scramble to try to ensure that my identity is safe.

- I filed an identity theft report with the Federal Trade Commission.

- I checked my credit reports for fraudulent or suspect activity, which, thankfully, are clean thus far.

- I placed a fraud alert on my credit record with each of the three credit bureaus. In theory, if someone tries to open an account under my social security number over the next year, I should receive a telephone call to verify my identity and stop the fraud.

- I’ve attempted to report the fraud to the Kansas Department of Labor, but so far I’ve had zero success. I cannot even reach a queue to be placed on hold. Each time I’ve called, at various points throughout the day, I’m told that all representatives a busy, that the hold queue is full, and that I should try again later, and then I’m disconnected.

Stories like mine and Kelly Maculan’s should serve as a serious wake-up call for state unemployment systems, which quickly need to reform and update. Under even the best of circumstances, we’re at least a step behind cybercriminals and identity thieves. Let’s at least make the fraud more of a challenge for them to accomplish.

This post originally appeared on the Ohio Employer’s Law Blog, and was written by Jon Hyman, Partner, Meyers, Roman, Friedberg & Lewis. Jon can be reached at via email at jhyman@meyersroman.com, via telephone at 216-831-0042, on LinkedIn, and on Twitter.